A 10-year-old female presents to the ED with high fever, cough, and trouble breathing. She reports feeling very weak and is carried into the ED by her mother. She has a history of asthma and uses an albuterol inhaler as needed. Her mother reports that she attended a baseball game two days prior with her father and grandfather, who are also in the ED with similar symptoms.

Exam: The patient responds to questions with grunts and withdraws from painful stimuli. She is taking short, shallow breaths and there are scattered rhonchi. Her abdomen is mildly tender to palpation and capillary refill is delayed (4 seconds). Her extremities are cool.

Vital Signs: HR 145 bpm, BP 84/52, RR 34 bpm, 104.2°F (40.1°C), pulse ox 90% (ambient air).

Clinical course: She is placed on oxygen (5L non-rebreather); oxygen saturation improves to 94%. IV access is obtained and she is given a bolus of isotonic saline 20 mL/kg. Heart rate decreases only slightly to 140 bpm, and there is minimal improvement in capillary refill. The patient’s cough worsens and she develops hemoptysis.

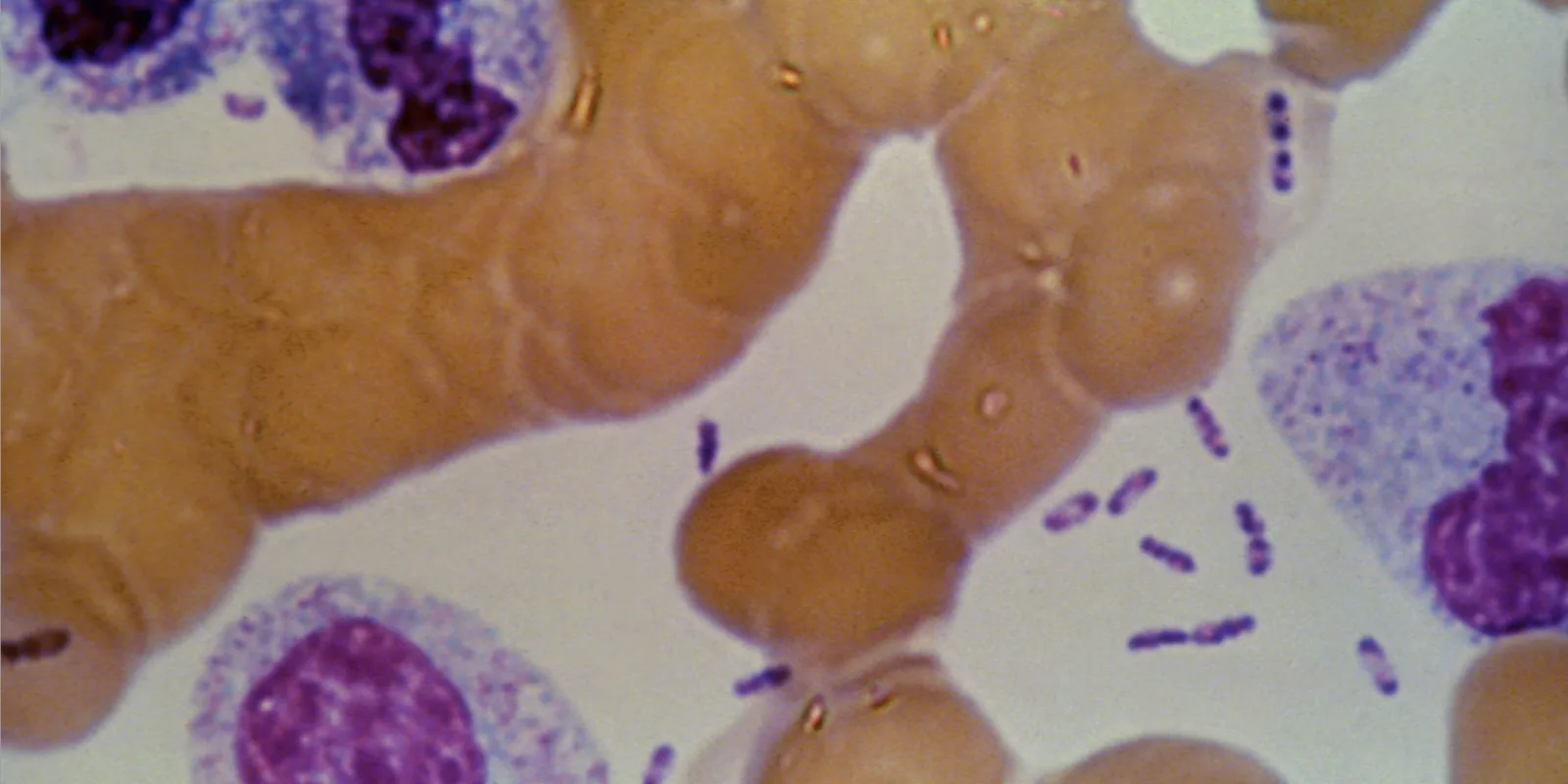

Initial Data: Manual differential and blood smear is conducted. The laboratory calls to report the presence of bipolar staining organisms in her blood. The organisms have a safety pin appearance on Giemsa stain (see Figure 1). CXR reveals bilateral, diffuse interstitial pleural infiltrates.

Based on these findings, what is the most likely diagnosis of this patient?

Anthrax

Tularemia

Hantavirus

Plague

This patient, her father, and her grandfather all have symptoms and an exposure history consistent with pneumonic plague and should be treated with antimicrobials immediately. Additionally, bipolar staining of the organisms seen in the blood culture is characteristic of Y. pestis.

Anthrax is caused by the gram-positive organism Bacillus anthracis; on gram-stain the appearance is described as “boxcars.” Tularemia is caused by Francisella tularensis, a gram-negative coccobacillus, and does not typically cause hemoptysis. Hantavirus is a virus and so would not appear on a gram stain of a blood smear. If healthcare providers suspect a patient has plague, they should begin antimicrobial treatment without waiting for confirmation of diagnosis. First-line agents for treatment of pneumonic plague include ciprofloxacin and gentamicin. Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague, remains naturally occurring in many countries including the western United States, and it is a Tier 1 bioterrorism select agent. Pneumonic plague would be the expected manifestation following a bioterrorism event, since the likely route of dispersal would be via aerosolization. In this case an epidemiological investigation would find there was an intentional release of Y. pestis at the baseball game these patients attended.

In addition to treating the ill patients, post-exposure prophylaxis should be considered for anyone who was potentially exposed to the intentional release (i.e. other attendees of the baseball game) as well as for any person who had close contact with symptomatic patients (e.g. patient’s mother, healthcare providers). Recent guidelines published by CDC describe treatment and prophylaxis options for plague. These recommendations include special population groups such as pregnant women, children, neonates, and geriatric and immunocompromised persons.

Resources:

Antimicrobial Treatment and Prophylaxis of Plague: Recommendations for Naturally Acquired Infections and Bioterrorism Response

CDC- Plague

CDC- Plague- Resources for Clinicians

Clinical case credit: Christina A. Nelson, MD, MPH; Katharine M. Cooley, MPH; David W. McCormick, MD, MPH

Image Source: CDC