On the first day of medical school, students are often asked what they are interested in. Upon receiving an ambiguous answer, the questioner often follows up with, “Ah, are you interested in surgery or not?” From the very beginning, medical students are asked to sort themselves into a category – a decision that subconsciously transcends their beliefs about their own capabilities. These beliefs follow students into their first day of anatomy lab, their first day learning how to suture, and their first day on surgery rotation.

On the first day of medical school, students are often asked what they are interested in. Upon receiving an ambiguous answer, the questioner often follows up with, “Ah, are you interested in surgery or not?” From the very beginning, medical students are asked to sort themselves into a category – a decision that subconsciously transcends their beliefs about their own capabilities. These beliefs follow students into their first day of anatomy lab, their first day learning how to suture, and their first day on surgery rotation.

I went into my third-year rotations with this preconceived notion that I was not the best in anatomy and that I had to have decided two years ago whether I wanted to do surgery or not. On my first day of surgery rotations, I had already effectively ruled out surgery as a career option based on preconceived notions of what surgery entails – long hours, a cast iron stomach, thick skin, and a bladder made of steel. I had ruled out a career option before I ever truly experienced it.

This changed during my first day on ENT service. I loved the diversity I saw in clinic: pathologies ranging from infections to fractured nasal bones to obstructed nostrils, patients ranging from infants to older adults. I expressed fascination to the two male residents I worked with, and one of them even showed me pictures from a neck surgery he performed.

“I can’t do that!” I exclaimed. The truth of the matter is, I had only watched a C-section as a pre-med student. How was I to know what I could and couldn't do?

The resident replied, “Of course you can!”

“But I’m not good at anatomy. I was not one of those kids who decided on surgery since day one,” I rebutted.

My resident reassured me, “Anatomy can be learned. So can surgery. You can do it.”

This moment made me realize that I did not give myself the freedom to explore surgery before thinking that I would be “bad” at it. As my 3-week ENT rotation flew by, I began to see the possibility of becoming an otolaryngologist. In the OR, I saw thyroidectomies, tonsillectomies, an orbital exoneration for squamous cell carcinoma, and a stapedectomy, among other awe-inspiring surgeries. In clinic, I saw what happens when a damaged recurrent laryngeal nerve causes vocal cord paralysis through nasopharyngoscopy. I got to see the patients pre-operation and post-op, and experienced the rollercoaster of emotions with my patients throughout the process.

By the end of my ENT rotation, my knowledge and comfort had steadily risen. I saw 10 patients on my last day of service, presented my patients to the attending, and helped write up their progress notes. I asked my attending for an evaluation, beaming with pride that I had accomplished a difficult feat of seeing so many patients in a specialty clinic — a task that I would not have been able to do merely a few weeks ago. My attending was shocked to hear that this was only my third week of rotations ever and complimented to the residents that I was performing well above expectations.

One female resident replied, “All medical students are supposed to see patients. Maybe not the students from the nearby medical school, but where I went to medical school we were all expected to see patients.”

My stomach sank. I had worked hard the past three weeks, and especially that day in clinic. Why were my accomplishments belittled? Of course medical students are expected to see patients, but I had seen 10 patients in one day. Why did it feel like we weren’t celebrating each other’s accomplishments? This feeling of hierarchy and competition may be a widespread phenomenon in medical training, but this was my first exposure to surgery. How was I to know if this was an isolated incident, or the culture of the field?

I left feeling disappointed on my last day of ENT service. For years I internalized that surgery can be demanding, cold, and unforgiving for female trainees. In 2017, only 17% of otolaryngologists are female. I was just starting to unravel my preconceived notions and envision a future in it for myself. But microaggressions such as these make me think twice.

So to all resident physicians, I ask that you recognize and encourage the medical students you see. Your medical students look up to you just as much as we do to attending physicians. Be kind and supportive — you were once in our shoes. No matter how burnt out or tired you are, your words, actions, and attitudes can be life-changing for students who are still deciding what specialty to pursue. To attending physicians, we are still learning. We are moldable. Teach us in a way that will motivate us to work harder and read more. Small encouragements, such as compliments about things we are doing well, and acts of kindness go a long way. To reverse the narratives about surgical fields and recruit the next generation of surgeons, the opportunity is in your hands.

As for me, “surgery or not surgery?” We’ll see.

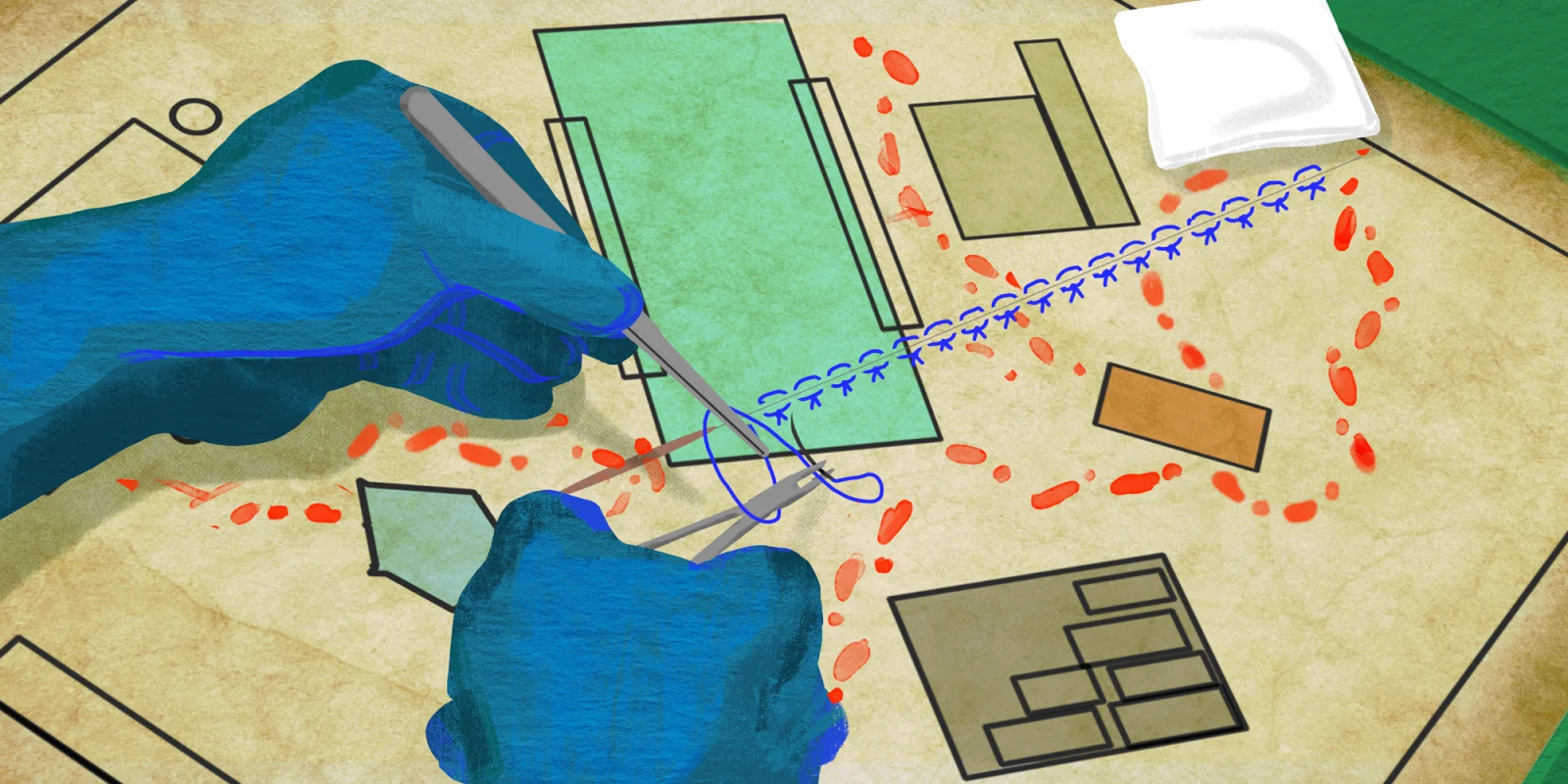

Illustration by Jennifer Bogartz