The HBO documentary “At the Heart of Gold,” concerning the Olympic girls' gymnastics scandal perpetrated by Michigan State University’s Dr. Larry Nasser, brought outrage, sadness, and nausea.

Michigan State is my alma mater.

The university's trusted administrators ignored the allegations and now Michigan State will join the victims and try to survive an avoidable nightmare.

The university will pay a half billion dollars to those that suffered. Imagine the scholarships that money could provide or the research that could be supported.

A black cloud will forever hover over the banks of the Red Cedar.

I thought of other scandals. The Jerry Sandusky incident at Penn State, the recent abuse of young children on Native-American reservations, and pedophilia in the clergy.

They have in common sexual abuse and the fact that nobody would listen to, or give credence to the victims.

I am a physician for amateur boxing and prior to being certified as a ring physician I had to view information supplied by SafeSport. I assumed the material would concern the protection of boxers from physical harm. But that was not the case. The majority of the information was about protecting athletes from sexual abuse.

According to SafeSport, 13% of athletes are subjected to some form of sexual abuse and that number is higher among elite athletes.

I read Sugar Ray Leonard’s autobiography. Leonard states that he was abused on two occasions. The abuse occurred when he was a formidable contender.

I refused to believe that anybody could or would abuse Sugar Ray Leonard. Sugar Ray, the Olympic gold medal winner, would knock the bastard into next week. I raised this question to a more seasoned fight doctor who said it was most likely true, and that abuse of athletes is very high.

Boxing is not excluded.

I fell into the same trap as those who refused to listen to the women.

Larry Nasser’s abuse of young women and little girls was first reported in 1997 and did not come to a halt until 2017. The athletes that complained were not taken seriously or were intimidated with fear of reprisal. The complaints of 1997 went nowhere. Their exploitation and suffering continued.

In the case of Larry Nasser, internal investigations were held, but nothing was found. That is no surprise. “Internal investigations” are an absurd oxymoron orchestrated for protection of an institution.

Eventually the abuse became so widespread that cover ups could no longer suppress the truth.

156 women spoke at Nasser’s trial and 300 women filed complaints.

The former president of the university, and the former women’s gymnastics coach, await a criminal trial — both are women!

It is incredulous, given the high incidence of abuse, that athletics did not come to a halt, and legitimate investigations begin at the first sign of trouble.

That Nasser’s abnormal behavior was tolerated, ignored or covered up is the real problem. Nasser will never see the light of day. He got 174 years. The sentencing judge called it a "death sentence," but “short eyes” don’t last long in prison. Equally egregious is the behavior of the “normal” people, the top-level administrators, who ignored or held self-serving internal investigations and thus protected the status quo.

Administration should not be allowed to hide behind the corporate. The defenders of the institution should be as severely punished as Nasser and perhaps more so. Were this the case, environments that provide the opportunity for such abuse, would become extinct.

Boxers say “you can’t fight crazy,” and the Nassers can’t be dealt with, but the administrators and beurocrats can be induced to do the right thing, especially if their career is on the line, not to mention a long prison term.

At a young age we are told not to be a “tattletale” or “snitches get stitches.” Whistleblowers have low status; they are reviled and usually met with little success.

There is a concern that accusations are without merit. This brings to mind the false rape allegations brought against the Duke lacrosse players.

Competent law enforcement uncovered the deception.

If the allegations against an individual are of a nature that an innocent life or lives could be ruined, professional outside investigations should be initiated at the fist sign of trouble. Corporations are not law enforcement agencies and lack investigatory depth. Consciously or subconsciously, decisions that are political, arbitrary, and expedient can mask as justice. That was the case at Duke.

Had outside investigators examined Michigan State in 1997 or Duke in 2006 these tragic events could have been avoided.

I recognize two types of whistleblowers, those that strive to protect the vulnerable and those that seek monetary gain.

For the latter I have little interest. Going after an institution for financial misconduct in hopes of a monetary reward has its place, but it's a high stakes game not unlike professional bounty hunters.

The whistleblowers who try to protect the innocent have my greatest respect. They gain nothing financially, suffer emotionally to protect others, and usually commit career suicide. They work alone but are on the side of the angels.

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha brought the Flint water crisis to light, thus sparing further lead toxicity in children. The pediatrician states “it took courage and fortitude to keep pushing against the tide. My credentials were questioned, and I was accused of causing ‘hysteria’ and trying to make the city look bad, when all I wanted was to get to the bottom of what was hurting my patients.”

Dr. Hanna-Attisha did not suffer career suicide but is now director of an initiative to assist the victims of the Flint water crisis. Her book, “What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City” describes the events.

Dr. Hanna-Attisha is an alumnus of Michigan State University. That makes me proud. It is a step toward MSU’s redemption.

A woman was listened to, but it wasn’t easy.

Along the same lines, it appears Boeing knew of the problems with the 737 Max jet a year prior to the fatal crashes. Were there any whistleblowers? Were they listened to? Were there “internal investigations?” The 346 dead people will never know, but perhaps their families should. Ethiopian Airlines and Indonesia Lion Airlines have raised questions. The FAA chief told Congress that working alerts “wouldn’t have changed either accident.”

Stay tuned on that one.

Abuse can masquerade as medical treatment. Nasser hid behind a physician's panoply. It is difficult to fathom that “vaginal adjustments” was an unquestioned procedure. We want to believe in the veracity of doctors, priests and other representatives of authority. We gravitate to, and take comfort in, denial.

A disturbing situation occurred early in my medical career. I was the member of a team of young doctors who had the opportunity to round with a famous internationally known visiting professor. The esteemed clinician-researcher would insist on repeating the rectal exam on all new admissions. The four of us had to stand around and watch.

We talked behind his back and wondered why he had to repeat such an exam. We concluded that he was a compulsive doctor’s doctor and that perhaps he had missed a cancer at one time in his career and it was for the patient’s benefit.

I have wondered about this for 40 years but while writing and thinking about this op-ed it hit me square on the chin and I realized that had he really been concerned for the patient’s welfare he would have performed a test for occult blood. This we always did, but this he never did.

The parents of the abused athletes fell into a specious trap of unquestioned belief in a prominent physician and I may have as well.

A long time ago a corporate attorney told me that whistleblowers are “roadkill that should be run over again and again then peeled off the asphalt. They are troublemakers.”

Whistleblowers may be tedious and annoying, but are very important, especially when humanity interfaces with lawyered-up corporate indifference. I see whistleblowers not as “roadkill,” but as a steadfast “canary in a coal mine.”

Dr. Olaf Kroneman is a nephrologist at the Southeast Michigan Kidney Center. He graduated from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, interned at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, then attended the University of Virginia to complete a residency in Internal Medicine. He completed a fellowship in Nephrology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. His work has appeared in literary magazines. Dr. Kroneman is a 2018–2019 Doximity Author.

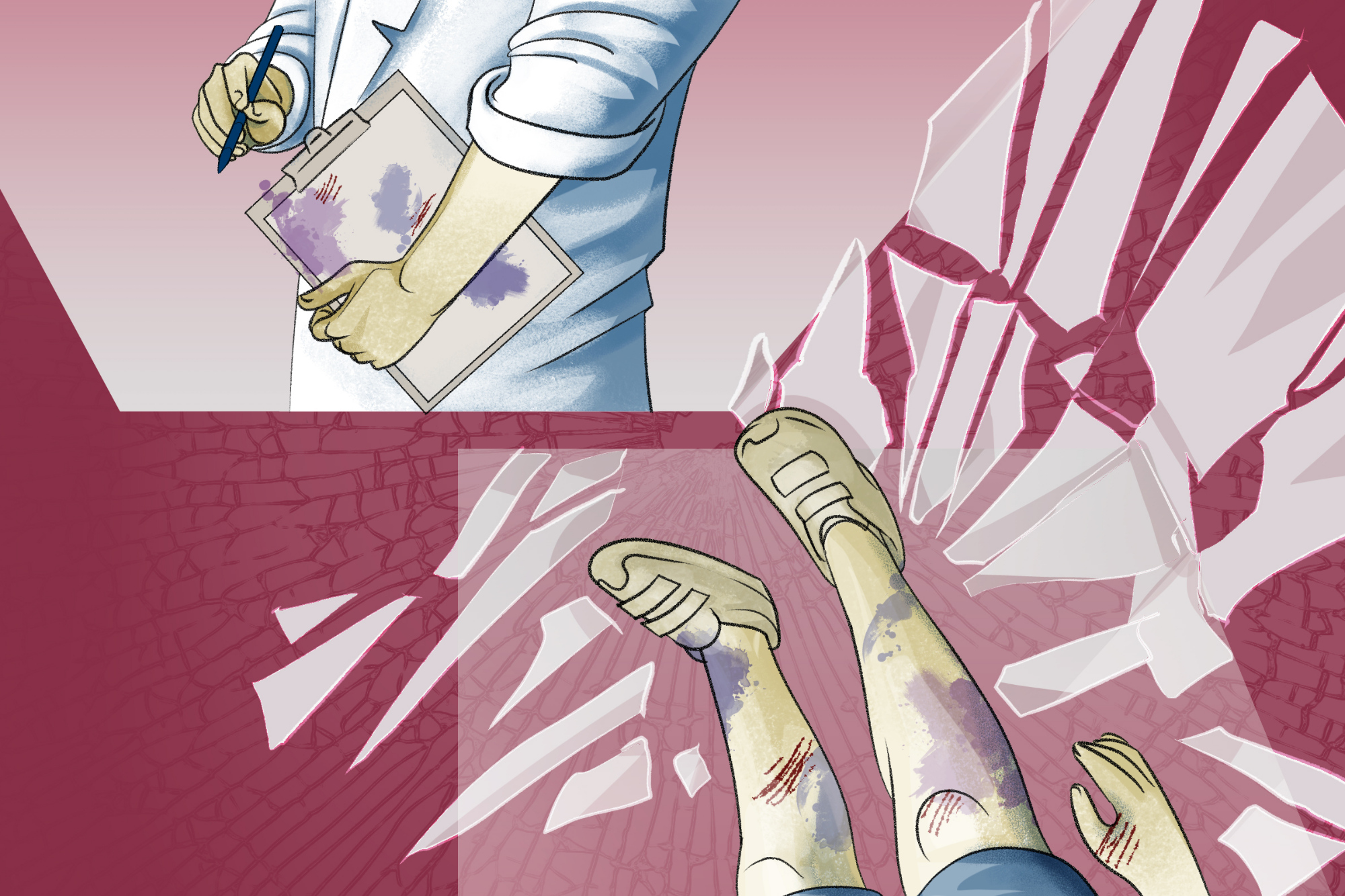

Illustration by April Brust