On the first day of anatomy lab, a non-dissection day meant to familiarize my class with the cadavers, my team accidentally broke our cadaver’s nose. I remember looking at the squished nub at the center of his ghoulish colored face and rushing home to cry. As much as I tried to appreciate the experience, anatomy lab never got much better. I hated the standing, the scent of formaldehyde that lingered in my hair, and the thankless task of scooping out fat or carving through rock-hard fascia for hours. The end of anatomy was a day of gratitude for me.

Understandably, then, I entered my surgery rotation with a mix of anxiety and dread. I had heard horror stories of surgeon personalities and lacked confidence in my physical endurance for the clerkship. Would I be able to answer any of the Pimp questions? Could I stand that long with my hands clasped to my chest? What if I fainted like I did doing my first lumbar puncture two months prior?

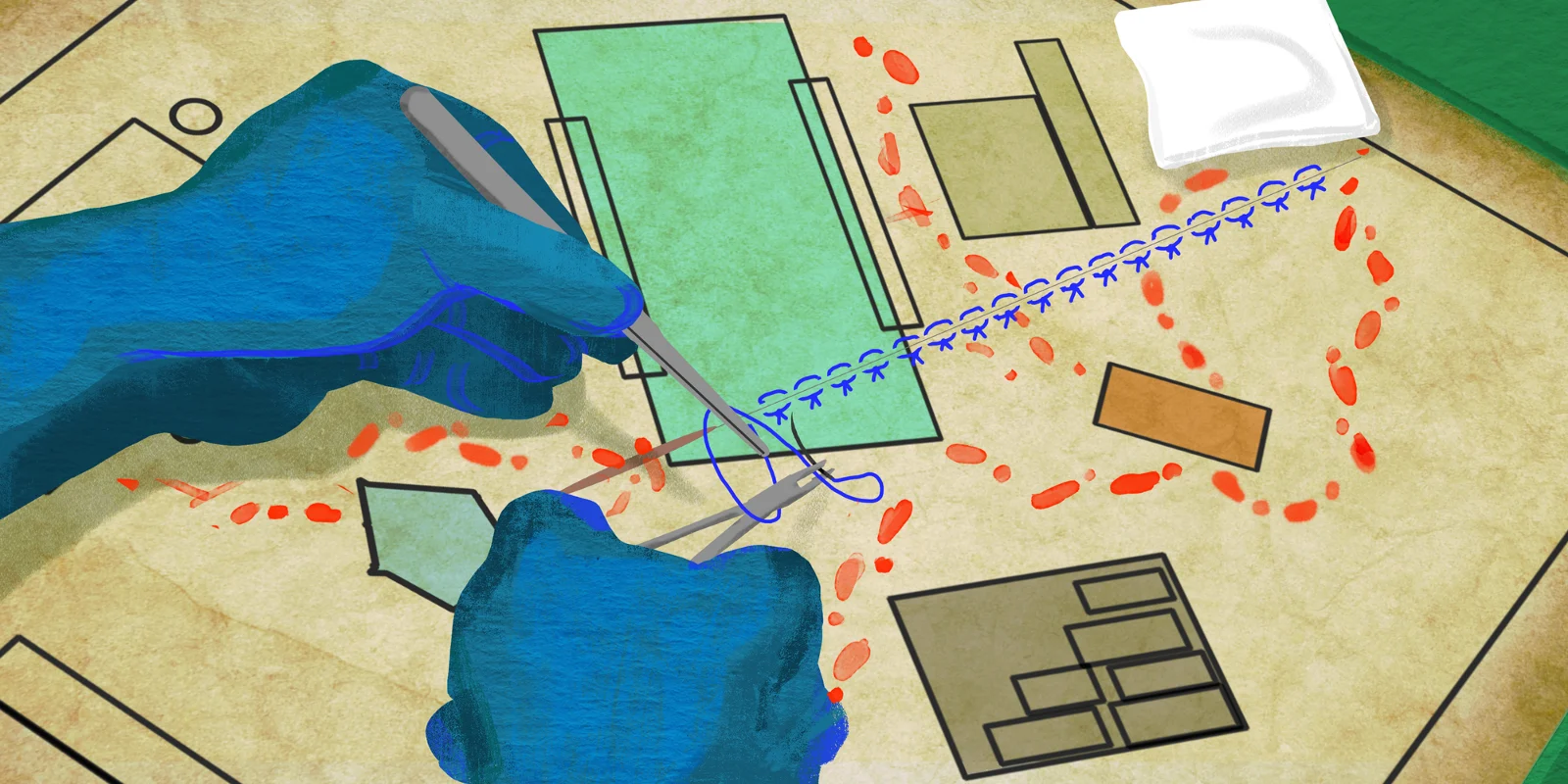

My first case was a pilonidal cyst, and my residents told me not to look up the definition before the procedure. Imagine my surprise when I turned from the two nurses coaching me through the sterile scrubbing process to find the patient’s butt cheeks freshly shaved and being spread apart evenly with medical tape. Two cases later, the surgeon finished up a port removal and left me to close the incision under the careful watch of the resident. With the needle driver shaking in my hand, I was off to the races from the first day.

To my absolute surprise, I fell in love with surgery. Despite having little idea of what most of the instruments were much less the procedures being done, the skill and artistry exhibited by the physicians in front of me left me breathless. I loved the quick dance of the scrub techs who were ready to offer the right tool the moment the surgeon’s hands opened for it. During complicated cases, I watched as surgeon’s shoulders and neck veins tensed at the same time as their motions became more elegant and precise. My back hurt for weeks just by cutting suture, and I could only imagine standing for years with my gaze fixed upon a small area of life-saving and life-ending potential.

Most significantly, my attitude towards anatomy completely changed. I had figured that surgery would turn rote; after all, it couldn’t take too many gallbladders before surgeons could remove the organ in their sleep. Unexpectedly, I realized that each patient is different, and that a strong foundation in anatomy is what allows expert surgeons to navigate the individual differences that anatomic abnormalities, body size, and diseases produce.

Many times it felt like I was navigating a foreign country, with language, culture, outfits, and customs that I had never encountered. My job was to soak up as much as I could and to adapt as fast as possible, much as I do when I travel. I relished every overwhelming moment. My knowledge base always felt much smaller than I wanted it to be, and I still haven’t quite figured out basics like how surgeons decide between electrocautery, suture, and clips. But once I entered the OR, I discovered a whole new world and couldn’t imagine my professional life outside of it.

Three weeks into my surgery rotation and three hours past the time I was supposed to go home that day, I got the notice of yet another trauma alert of the evening. The boy was a passenger in a motor vehicle crash with his uncle, and both were airlifted to the hospital. Although the boy’s workup was negative, he had an impressive forehead laceration. Somewhat as a nod to the fact that I had waited with the patient after the rest of the team had left, an ER doctor gave me the opportunity to close the laceration. I was both thrilled and acutely aware that the boy was conscious and staring straight at me during the entire process.

As I zeroed in on the patient’s wound and tried to will the mastery of the experienced surgeons into my body through sheer prayer, the ER doctor leaned over me and whispered, “There will come a day when your hands don’t shake anymore during procedures — I promise you that.” I can’t wait for that day.

Riana Kahlon is a fourth-year medical student at the UCF College of Medicine in Orlando, Florida. She is passionate about healthcare access, technology, narrative medicine, and her love for dogs.